Especially for our newsletter subscribers our article about the Royal Road. Enjoy!

In ice hockey, there’s such a thing as the Royal Road, referred to by some as the most important line on the ice. Most have never heard of it, but research shows that using this Royal Road in ice hockey leads to more goals. Can this be applied to floorball?

What is the Royal Road?

It’s about goals, both in ice hockey and floorball. Score more than your opponent and you win the game, it’s as simple as that. In larger sports, such as ice hockey, statistics start to play a bigger role every year (although we can also see this development gaining traction in floorball). All numbers are being looked at, such as the number of shots on goal, but also the quality of each shot.

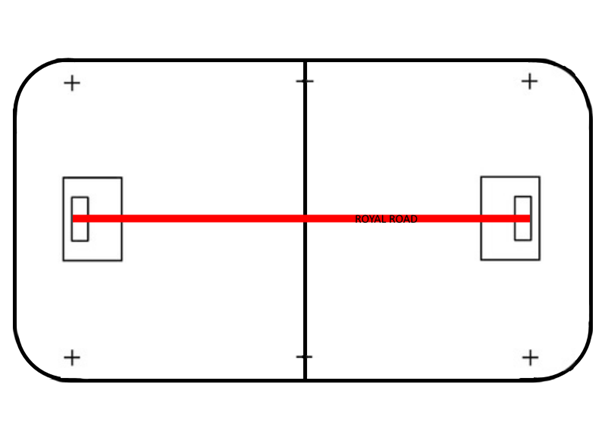

This is where the Royal Road from ice hockey comes into play. In the USA, Stephen Valiquette watched about a hundred games of the NHL season 2014/2015 and analyzed the goals scored. After completing the analysis, he launched the term Royal Road: the imaginary line between the two goalkeepers, which splits the field into two parts (in the length of the pitch).

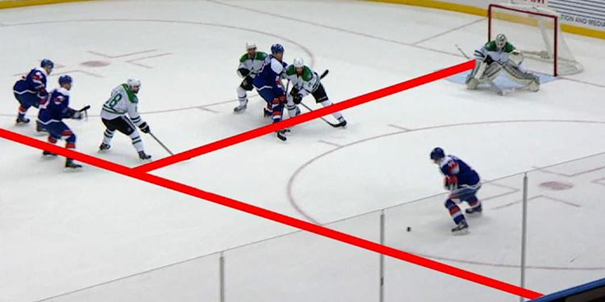

In the image above, it concerns the line from the goalkeeper (top right) to the tangent plane with the other line, or have a look at the red line in below’s image.

Valiquette states that shots ‘using the Royal Road’ have a greater chance of becoming a goal. This Royal Road changed everything – in ice hockey.

In short: if the puck had crossed the Royal Road prior to a shot, the chance that the shot would become a goal became more than ten times greater. An enormous number, but how can it be explained? For that, we’ll start with something he named green goals.

Green goals

Valiquette observed a number of different scenarios in which the puck crossed the imaginary line. He divided those scenarios into two categories: the dribble and the (cross)pass. As soon as the puck crossed this line, the Royal Road, the goalkeeper had to adapt to the new situation. This is the moment when the chance of a goal multiplied tremendously.

When a goalkeeper has its eye on the puck and nothing changes, he’s able to keep a perfect position, both in positioning himself in the goal and keeping his body position right. However, this changes when the goalie is forced to move to a new position – for instance directly after a cross pass is being given.

While moving to a new goalkeeper’s position, the goalie must both protect the goal, keep his eye on the puck and coordinate his movement (note: where ‘puck’ is said, you can also read ‘ball’). The goals that followed from these actions were called Green goals: goals where the goalkeeper had less than half a second to see the shot coming.

And guess what? A whopping 76% of all goals were Green goals.

What else turned out to be? Only a quarter of all shots per game was a ‘Green shot’ – the rest consisted of ‘Red shots’, shots in which the Royal Road was not in play. So the smallest number of shots led to the highest number of goals, as 25% of the shots where Green shots, while 76% of the goals were Green goals.

Returning to the introduction: a team does not necessarily have to have the highest number of shots on goal, it is more about the quality of the shots.

What are the differences between the Royal Road and Green goals? A Green goal doesn’t necessarily have to have gone over the Royal Road, it’s about the goalkeeper having less than half a second to see the shot.

The types of Green goals divided into categories

It is almost impossible to perform Valiquette’s work in floorball: watching a hundred games and writing down what kind of goals are scored. This is why we take the figures for ice hockey again.

Valiquette divided the Green goals into seven categories. Below we discuss them, if possible with an example from floorball. With this, we also start answering the question if the Royal Road can be used in floorball. To repeat: 76% of all goals were scored from a Green shot/rebound while they made only up 25% of the shots.

1. Passes over the Royal Road (22%)

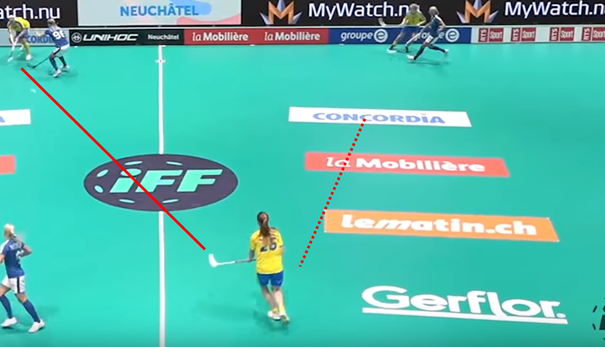

How do you maximize your chances of scoring a goal? Make a cross pass, so a pass over the axis (the Royal Road). The goalkeeper has to react in order to protect the goal properly and in this situation has more difficulty in both positioning himself (or herself) and keeping an eye on the puck (or ball).

The image above is from the Champions Cup final 2020 between Storvreta and Wiler-Ersigen. Immediately after the pass, the goalkeeper is in a hopeless position for the shot from the left.

2. Screens (10%)

Screening, i.e. removing the goalkeeper’s view of the game by standing in front of him, leads to goals. In the research of Valiquette, it even leads up to 10% of all goals. When screening, the goalkeeper cannot see the puck coming.

Within floorball, this could theoretically even lead to an even higher percentage of goals, due to the fact that the scoring area – the part of the goal not covered by the goalkeeper – seems to be bigger in floorball than in ice hockey. This has to do with ice hockey goalies being able to cover a bigger are of their goal, although the goal is slightly bigger than in floorball (2,16 m² compared to 1,84 m² in floorball).

In the bronze final of the WFC 2019, Finland scored the equalizer thanks to this goal from Veera Kauppi, but the main role is reserved for #21 Ella Sundstrom, who has a good screening and makes the goalkeeper’s work a lot more difficult.

3. One-timers on the same side of the Royal Road – 9%

In the third category, the Royal Road is not in use. It concerns shots from behind the goal, which are brought in front of the goal and shot directly. Valiquette counts this as a Green goal since the goalkeeper can only react to the shot for less than half a second.

Why are there fewer goals in this category compared to the cross pass? Because the goalkeeper, even if he doesn’t see the puck coming (everywhere where ‘he’ is, ‘she’ can be read as well), is often already fairly well-positioned. He doesn’t have to move from left to right.

In the WFC 2018 final between Finland and Sweden Alexander Galante Carlström scores from a pass by Emil Johansson, being given from behind the goal. Thanks to the power play situation Galante has the space to shoot, but thanks to his speed he doesn’t give goalkeeper Eero Kosonen any chance to anticipate the ball, let alone stop it.

4. Broken plays – 9%

By broken plays we mean the chaotic situations in the slot of the field, directly in front of the goal. Moments like this happen if there is a duel just in front of the goalie where the puck can actually go in any direction. Every shot in this situation is a surprise for the goalkeeper.

5. Dribble over the Royal Road (8%)

Number 5 is similar to Category 1, the cross pass, but in this case, it is more of a cross ‘walk’ movement. The idea behind it is the same: as soon as the ball passes the royal road, the goalkeeper has to choose a new position, sliding from left to right or from right to left. At that moment, the goal is less well guarded than usual and the goalkeeper cannot use 100% of his capacity to stop the shot.

In the example above, Emelie Wibron walks up in the middle, where she gets a lot of space (see image 1). She passes the Royal Road, pulls the trigger and scores 5-4, with which she brings Sweden to the finals of the WFC 2019, at the expense of Finland.

6. Deflections 8%

Deflections arise from Red shots, i.e. shots in which the goalkeeper has plenty of time to position himself and keep an eye on the puck. In fact, you might even call these shots ‘bad’ shots, but thanks to deflections, there are still situations in which the goalkeeper has no chance. 8% of all goals made in the matches watched by Valiquette are deflections.

7. Green rebounds 8%

8% of all goals come from a Green rebound; a rebound that occurs after one of the above Green shots has been applied. The goalkeeper has little time to react to the rebound or even has no idea where the puck is, so a rebound is relatively easy to score in this case.

In the above situation, Sweden first gets a chance from the left (still 1), followed by a rebound from the right (still 2). Twice the team does not score, but the second rebound (still 3) leads to the goal.

Why this research is (not) useful for floorball

Since floorball once originated as summer training for ice hockey, it is logical that the sports are very similar. Including the goalkeeper the teams play 6-vs-6, there is the possibility to switch players at any given moment, the goal is placed inside the field making it possible to play the puck/ball behind the goal and oh yes – both sports are played with a stick. So it’s clear ice hockey and floorball are similar to a certain extent.

So for you, being a floorball player: is this research useful or not?

Well… Yes and no. We’ll explain.

Yes:

- As the above example shows, a lot of ice hockey situations are recognizable in floorball. The chance of scoring a goal is increased – in ice hockey – by striving for Green shots and Green goals as much as possible and it seems that this is the same in floorball;

- It makes sense. It seems like a weak argument, but every goalkeeper will know that a shot from a cross pass is extremely difficult to stop, every defender will know that you want to stop a dribble through the slot, and every striker will know that he has to be ready for rebounds, both in ice hockey as in floorball;

- The results prove a lot of the goals in floorball are Green goals. So why isn’t it 100% “proven” yet? Because the number of matches and summaries we have looked at for this article is too small to obtain significant results.

No:

- Following on from the above: Valiquette watched about a hundred NHL matches. How many floorball games did we watch? Far from enough to be sure that the Royal Road and Green goals are a thing in floorball.

- In ice hockey, we expect the goalkeeper covers a bigger part of the goal than in floorball. Yes, the goal is bigger, but what’s more importantly: the goalkeeper has bigger pads, a wider collection of protective gear, a stick and ice skates, making the area of goal covering bigger. This leads to the following: a counter in which a player goes towards the goalkeeper on his own might, therefore, be easier to stop in ice hockey than in floorball. In floorball, this would reduce the need to pass over the Royal Road.

Summary

Valiquette stated that Green shots/rebounds accounted for more than three-quarters of all goals scored, while only a quarter of all shots fell into the Green shot category. In an average NHL match, around 22 out of 30 shots were Red shots. Out of the remaining 8 Green shots, three-quarters of the goals scored were made!

It may very well be that a large part of his theory is directly applicable to floorball, because the sports are so similar. It would be fantastic to investigate this any further, but we probably have to wait for it until our sports becomes on the level of ice hockey.

What do you think?

Is this useful for floorball, are you going to apply it in your training sessions and matches, or is it not possible to say something about the Royal Road and Green goals in floorball?

Let us know, via social media or Patreon!

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel